These pages are being constructed as a theoretical and practical resource for teachers who wish to incorporate more of the body, deep ecology and the arts into their teaching work. They are based on my own training in these fields and productive discussions with:

Llewellyn Wishart, Lecturer in Early Childhood Education, Deakin University and Certified Body-Mind Centering® Practitioner,

and

Alex Nicolson, my partner and master teacher of the Alexander Technique.

Continued from Part 3…

The Arts in Education

Misconceiving the arts as disembodied:

The fact that the arts and arts therapies are constantly required to justify their existence in terms of empirical “evidence-based” criteria shows just how much we have disconnected ourselves from our aesthetic nature. But is it enough just to squeeze artistic intelligence into the crowded competition of intelligences?

Wayne Bowman (2004) presents a stinging critique of the practice of adopting “multiple intelligences” model in order to claim “an intelligence” for music to “vindicate the educational integrity of artistic undertakings”. He describes this “strategic” re-characterization of music as still “abstract, mental, cerebral, disembodied”.

“What we have not done, precisely, is to question the nature of the divide (cognitive/emotional) itself: this stubborn dichotomy between knowing that counts and that which does not…” (p.29)

“Easy though it has become to pay such things [embodiment] lip service, the habit of treating body as the disavowed condition of knowledge (the subordinate counterpart of mind) is an extraordinarily difficult one to shake…deeply built in.” (p30)

Bowman exposes the misconception that music does for feeling what logic does for thought, as if they are “mutually exclusive hierarchically related opposites”. (p31):

“Music is a valuable cognitive resource not because of what it teaches us about the disembodied metaphysical realm of feeling…but what it shows us about the profoundly embodied and socioculturally situated character of all human knowing and being…” (p31).

If an art such as music, which is naturally associated with movement, is taught largely from visual notation, musical concepts and listening to music while sitting in classrooms, it is effectively eviscerated. Even children who excel at performance can be cut off through this kind of teaching from their own expressive and improvisatory capacities.

The experience of “flow” described in arts engagement is often mistaken for “concentration”, or becoming so focused on an activity to the extent of losing oneself, as if that is something to aspire to. True immersion in art making is not disembodied, but entails a simultaneous and embedded apprehension of one’s whole-self-in-activity-in-the-whole-world – a multisensory-motor integration.

Pause for a moment…

…consider your relationship with arts expression:

What was your experience of art-making at school?

What would your “timeline of artistic expression” look like?

How do you feel now about expressing yourself through arts such as expressive dancing, song writing, music making, writing poetry, drawing, painting…?

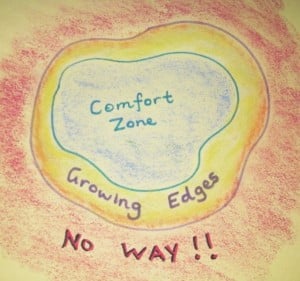

Which arts modalities are in your “comfort zone”? Which are on your “growing edge”? Which are in your “No way!” zone? (see the Creativity Contour Map below).

The arts, imagination and self-transformation

The imagination, which has been endangered by both the hegemony of the rational and the invention of technologies that supply us with pre-packaged images, has always offered human beings a rich source of knowing. Even Francis Bacon, to whom we attribute the epistemological birth of empirical science, “recommended the use of such figurative devices as aphorisms, illustrations, fables and analogies…” (traditional tools of gnostic mysticism and religion) because they “might help to interrupt entrenched beliefs by opening up imaginative possibilities” (Davis, 2004, p.68).

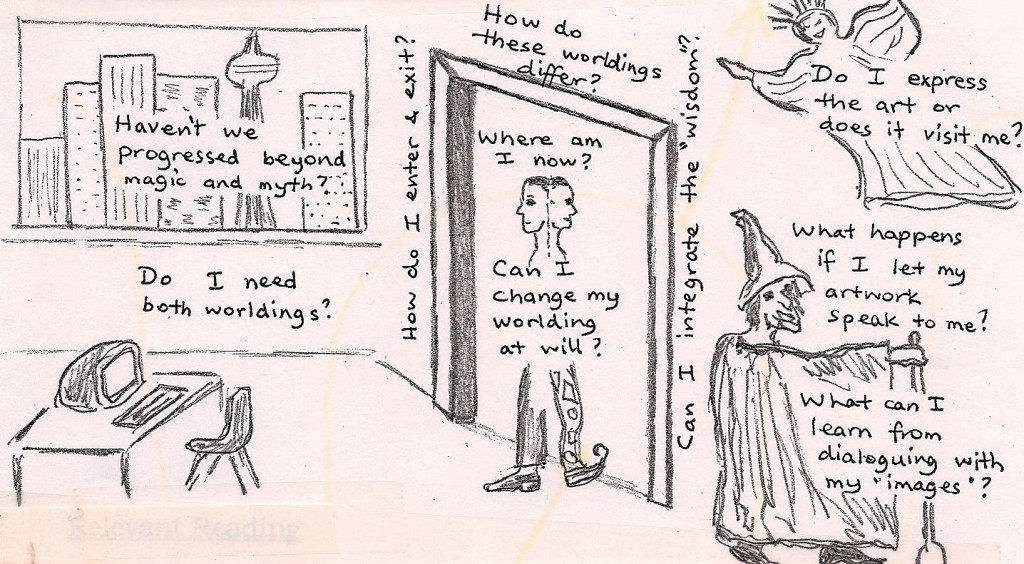

Embodied engagement with the arts offer us an “alternative experience of worlding” in which the imagination is key (Knill, 2000) – transitioning from our ordinary consensus reality into the kind of knowing referred to as “poiesis” by the ancient Greeks (Levine, 1999). Although this state can be associated with magical thinking more characteristic of gnostic mysticism (Davis, 2004), a post-rational poiesis avoids the literalism of pre-rational thinking without abandoning aesthetic knowing.

Alternative experiences of worlding present us with some questions…

Engaging with the arts therefore offers us places of playful not-knowing, ways of trying out new ways of being, subjunctive spaces of “as if” (Faire, 2004; Sumara & Davis, 2007) in which transformation of habitual patterns becomes possible.

The practice from Expressive Arts Therapy (Knill et al, 2005) of dialoguing with one’s emergent artwork imbues the art with an oracular role that does not necessitate literal belief in supernatural deities. It allows intuitive processes to foreground that would otherwise be invalidated by the mundane and dominant scientific world view (Faire, 2012).

Extending the reach of participatory art making beyond the infant years, and away from the secondary divide between mass audience and elite performer (characterized by a judgmental aesthetic), would allow children to retain this vital connection to poiesis into adulthood.

Artistic improvisation as a life skill

“Improvisation, with its emphasis on risk, responsiveness and relationship, is at the heart of the artistic process…”. Art-based researchers “rely upon skills that are central to improvisation, such as an openness to uncertainty, an attunement to difference and the aesthetic intelligence necessary to track significance.”(Sajnani, 2012, p.79).

Sajnani quotes Knowles (2010, p.5):

“When the one economic constant, ironically, is instability; when all aspects of our lives are driven by exponentially quickening technological change; and when education is increasingly under pressure to train people for jobs that by the time of their graduation are often no longer needed, it is increasingly the case that the best performances – human, corporate, or technological – are improvised.”

“…being skilled in improvisation increases one’s capacity to remain flexible and responsive amidst chaos while acknowledging (yet not submitting to) the urge to order, and to tolerate the uncertainty that comes with not knowing how your plan will turn out…” (Sajnani, 2012, p.82).

Improvisation “functions as a kind of ‘disciplined empathy’” (Sajnani, 2012, p.83).

Personal story

For many years over the 90’s to mid 00’s Alex and I were part of a monthly community gathering in which people came together to improvise through music and movement. We called it “Sound and Dance Conversations – Soundasations” and we met in various halls over that period, from Mosman to Artarmon to Northbridge. I documented this phenomenon in a little book <http://www.zulenet.com/ecosomatics/soundasations/default.html>

We had no leader of this group, and communications were founded upon sound-and-movement interactions. Sometimes words and songs and dramatic enactments would emerge out of the music-dance, and there would be a natural ebb and flow of “pieces” which seemed to create themselves.

At one stage I did some simple research into why people kept coming to this gathering. The responses fell into loose categories/themes, which I could sum up as “spontaneous play”, ”tribal connecting”, ”ancient earthy ritual”, ”healing self expression” and “joy”. When I look back on it through the lens of attachment theory it becomes possible that this gathering met a deeply therapeutic need: we may have been reparenting ourselves with these “protoconversation-like” soundscapes. It did feel to me like being “held” by the group. I think this is particularly potent when something I call “looping” arises: the music feeds the dance and the dancers inspire the musicians…until neither is leading.

I joked about this gathering that at the time I was training to be a “Music Therapist” while all the time this other thing was happening around me in which there was no “therapist”!

“It has gradually dawned on me that the creativity of human spirits engaged in the process of freeing themselves cannot be confined within a narrow definition of “therapy”. When our culture (with its labels of performer/audience, therapist/client, clergy/layman) failed to provide us with what we needed, we invented our own vehicle for growth, self-expression and spiritual renewal…” (Faire, 2002).

Arts expression in the development of empathy

The wellbeing of children begins in infancy, as has been well documented in the literature on attachment theory (Cassidy & Shaver, 2008). Non-verbal communication between infant and primary caregiver (protoconversation and motherese) build the rapport that supports secure attachment (Malloch & Trevarthen, 2009). The quality of the bonding relationship with a primary caregiver provides the template for subsequent attachment styles with peers, teachers and future partners (Feeney, 2008). The psychohistory of parenting testifies to the intergenerational nature of attachment disorders (Grille, 2005) and many children in Australia fail to receive this vital validation as infants.

Current early intervention strategies focus on mothers’ internal working models, parenting behaviours and capacity for reflection (Berlin et al, 2008). However, non-verbal modalities of communication such as the arts are potentially powerful transforming agents in an infant’s neurological, social and emotional development (Creighton, 2011).

This is because the essential communicative elements of the arts themselves grow out of our earliest experiences of intersubjectivity: the carer-infant “protoconversations” (Malloch & Trevarthen, 2009). These are mediated through sound, gesture and touch-based “vitality affects” which communicate felt-senses through their dynamics. Arts such as music, which contain these vitality affects or “essentic forms” (Clynes, 1986), therefore offer us an opportunity for both early and later intervention in dysfunctional mothering processes (Warja, 1999).

Arts Therapies in Schools

Currently, arts therapies such as music therapy are not part of most mainstream schools, or, at best, are considered adjunct therapies for children with “special needs”. The school counseling framework is focused on verbal therapies such as Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (Urbis Report, 2011, p68).

Providing access to the arts therapies to all children and adolescents as part of their school experience would add a valuable non-verbal dimension to the resources for both prevention and early intervention. Based on playful interactions between children, arts materials and therapists, they support emotional expression, relationship development, communication and empathy. Arts engagement within a safe, non-judgmental environment can provide non-verbal, validating “proto-conversations” to nurture children’s self esteem and build relating skills (Karkou, 2009).

What could we be doing differently?

What might we still be doing that interferes with embodied aesthetic expression?

– Assuming that teaching of the arts is an add-on module?

– Passing on judgmental aesthetics that potentially extinguish spontaneous creative expression in children?

– Focusing on creating expert artists/musicians/dancers or appreciative audiences at the expense of the expressive capacity of every child?

– Over-emphasizing visual musical notation at the expense of playing and improvising by ear?

– Separating music from movement/dance?

– Underestimating the importance of arts-based conversations in building the capacity for intersubjectivity and empathy?

What can we intend and enact more fully/differently in terms of arts expression? (our suggestions):

– viewing the arts as essential forms of human expressive and communicative capacity not just about performance;

– being mindful of aesthetic and intersubjective aspects of content;

– improvisation at the heart of arts expression;

– art making and journaling as self-reflection time;

– practices of aesthetic appreciation;

References

Berlin, L.J., Zeanah, C.H. & Lieberman, A.F. (2008) Prevention and intervention programs for supporting early attachment security, Chapter 31 in Cassidy & Shaver (below).

Bowman, W. (2004) Cognition and the Body: Perspectives from Music Education, p.29 in L. Bresler (Ed.) Knowing Bodies, Moving Minds: Toward embodied teaching and learning, Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Cassidy, J. & Shaver, P.R. (Eds. 2008) Handbook of Attachment: theory, research, and clinical applications, New York, Guilford Press.

Clynes, M. (1986) Generative Principles of Musical Thought: Integration of Microstructure with Structure. Principle 3: Essentic Forms. http://www.microsoundmusic.com/papers.html?bpid=8876

Creighton, A. (2011) Mother-infant musical interaction and emotional communication: A literature review. Aust. J. Music Therapy, 22:37-56.

Davis, B. (2004) Inventions of Teaching: A Genealogy, Mahwah, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

Faire, R. (2002), ‘Soundasations – Sound and Dance Conversations: The story of an evolving community improvisation ritual’. In Music Alive, the Community Music section of Music Forum, 8/2, 34-35, December-January. http://www.zulenet.com/ecosomatics/Soundasations/default.html

Faire, R. (2004). Myself: How to be as if: A Review, Poiesis: Journal of the Arts & Communication, 6, 176-8.

Faire, R. (2012). “The Presentation”: an intensive arts-based rite of passage adapted for the training of Music Therapists. Voices: A World Forum For Music Therapy, 12(1). https://voices.no/index.php/voices/article/view/630/518

Feeney, J.A. (2008) Adult romantic attachment: Developments in the study of couple relationships, Chapter 21 in Cassidy & Shaver (above).

Grille, R. (2005) Parenting for a Peaceful World, Sydney, Longueville Media.

Karkou, V. (Ed. 2009) Arts Therapies in Schools: Research and Practice, London, Jessica Kingsley.

Knill, P (2000) The essence in a therapeutic process: An alternative experience of worlding? Poiesis, 2: 6-14.

Knill, PJ, Levine, EG and Levine, SK. (2005) Principles and Practice of Expressive Arts Therapy: Toward a Therapeutic Aesthetics, London, Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Knowles, R. (2010). Improvisation. Canadian Theatre Review: Improvisation, 143(1), 3-5.

Levine, S.K. (1997) Poiesis: The Language of Psychology and the Speech of the Soul, London, Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Levine, S.K. (1999) Editor’s Introduction, Poiesis, A Journal of the Arts and Communication, 1: 2.

Malloch, S. & Trevarthen, C. (Eds) (2009) Communicative Musicality: Exploring the basis of human companionship. New York, Oxford University Press.

Sajnani, N. (2012) Improvisation and art-based research. Journal of Applied Arts & Health, 3(1),79-86.

Sumara, D. & Davis, B. (2007) Subjunctive spaces of curriculum: On the importance of eccentric knowledge. Curriculum Matters, 3(1), 79-91.

Urbis Report (2011) Literature Review on Meeting the Psychological and Emotional Wellbeing needs of children and young people: Models of effective practice in educational settings, prepared for the Department of Education and Communities. https://www.det.nsw.edu.au/media/downloads/about-us/statistics-and-research/public-reviews-and-enquiries/school-counselling-services-review/models-of-effective-practice.pdf

Warja, M. (1999) Music as Mother: The mothering function of music through expressive and receptive avenues, Ch 9 in Levine, S.K. & Levine, E.G. (Eds). Foundations of Expressive Arts Therapy: Theoretical and clinical perspectives. Jessica Kingsley, London